Common Errors during Root Canal Treatment

Endodontic procedures are intricate and require precision, attention to detail, and a thorough understanding of root canal anatomy and physiology. Despite advancements in dental techniques and technology, procedural errors remain a significant challenge during root canal treatment. These errors can compromise the success of the treatment, leading to discomfort, reinfection, or even tooth loss for the patient.

This blog explores common procedural errors during root canal therapy, including access opening, canal shaping and cleaning, and obturation. Challenges range from treating the wrong tooth or missing canals to complications like ledge formation, instrument separation, or irrigant mishaps. Understanding these errors, their causes, and prevention strategies helps clinicians achieve higher success rates and better patient outcomes.

Classification of Procedural errors:

- Related to access opening of the pulp space

- Related to canal shaping and cleaning

- Related to obturation

I. Procedural errors related to access opening of the pulp space

The main errors and challenges faced during access opening procedures are as follows:

1. Treating the wrong tooth:

This can occur due to an incorrect history or an improper diagnosis of the tooth. Failing to consider radiographic evidence and relying only on clinical symptoms often causes errors. This is especially true in cases of referred pain. To ensure accurate diagnosis and treatment planning, a detailed history, thorough clinical examination, and radiographic evidence must be considered. Pre-marking the tooth to be treated can further reduce the chances of treating the wrong tooth. Moreover, preparing the initial access cavity before placing a rubber dam can help prevent such errors.

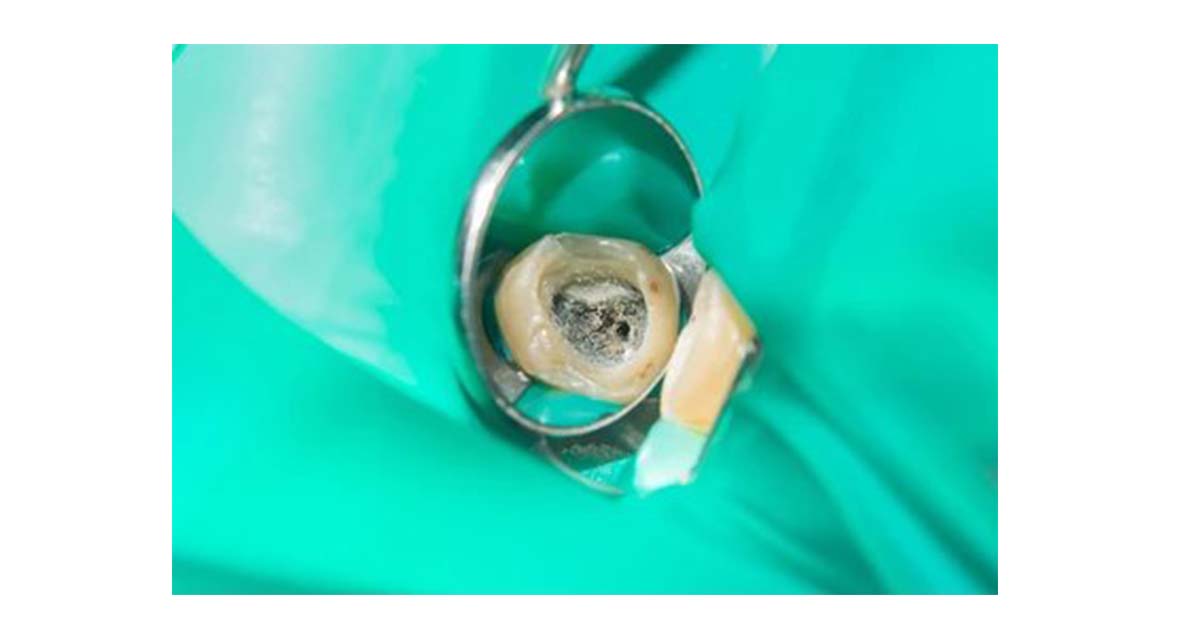

2. Incomplete removal of caries:

Leaving caries partially untreated can result in a weakened tooth structure even after endodontic treatment. Clinicians often focus on removing infected carious tissue but may overlook affected areas. This can lead to reinfection and treatment failure due to secondary caries and coronal leakage. Therefore, complete removal of the carious lesion should be a primary focus before proceeding with the access opening.

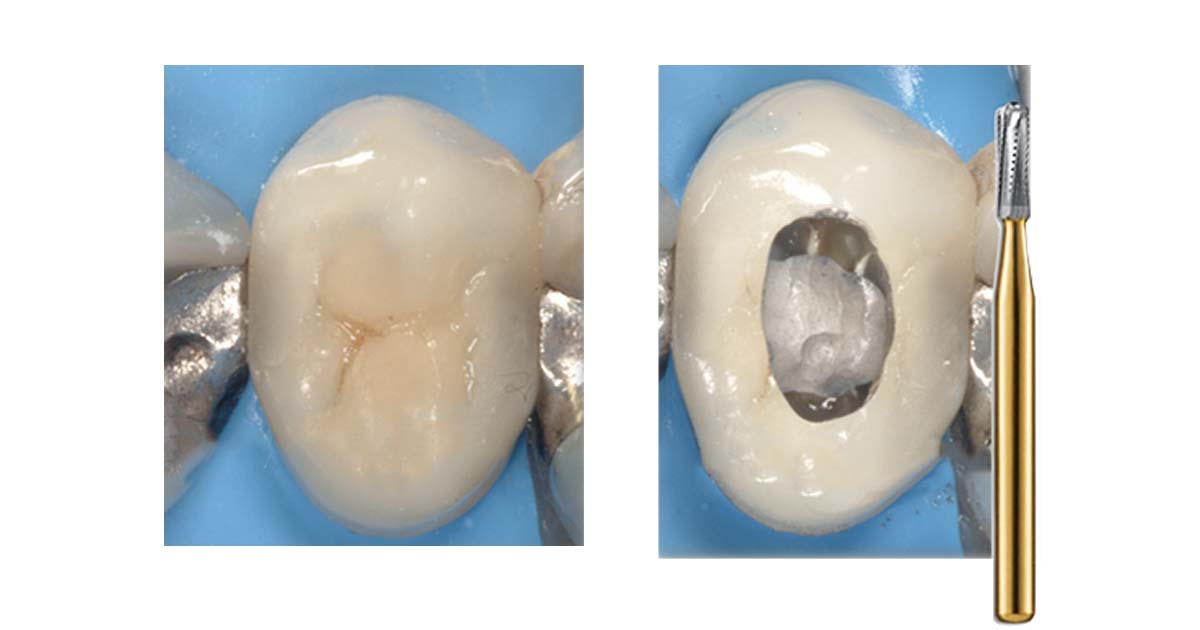

3. Access opening through full-coverage restoration:

When a tooth requiring endodontic treatment already has an existing crown with a good marginal seal, crown removal may not be necessary. However, maintaining proper bur orientation and parallelism with the tooth’s long axis during access opening can be challenging. Failure to do so may lead to incomplete caries removal, perforations, or inadequate cleaning and shaping, ultimately causing endodontic failures.

4. Inability to locate extra canals (missed canal orifices):

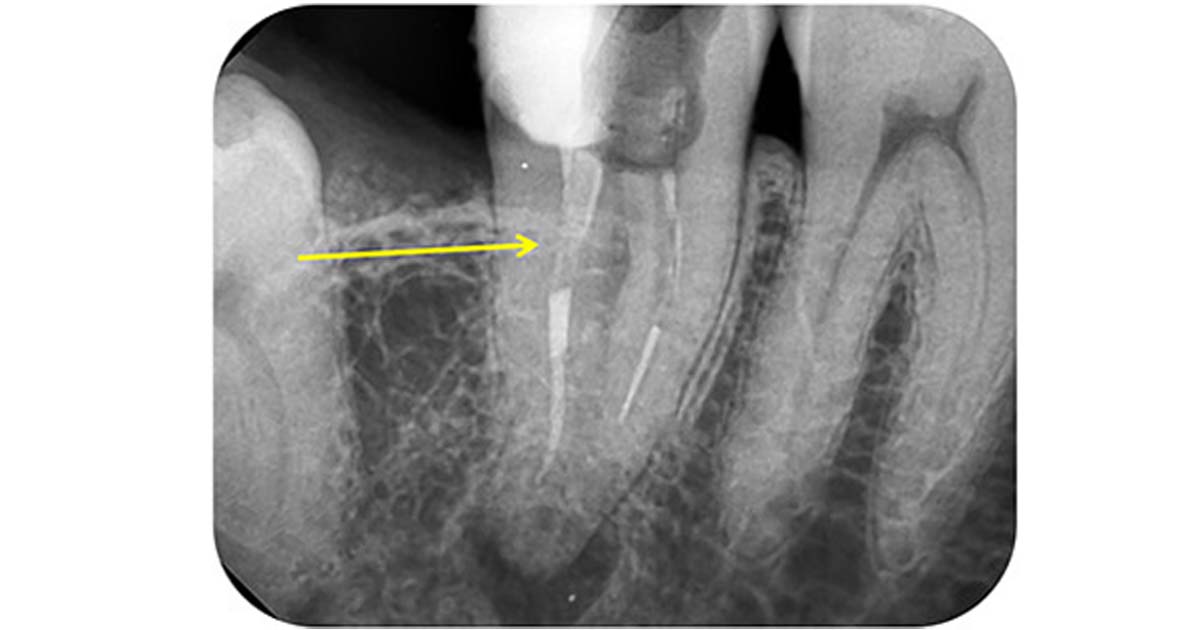

Failing to locate all canals is one of the primary reasons for endodontic failure. This often arises from insufficient knowledge of canal anatomy, improper access cavity design, or incomplete deroofing of the pulp chamber. Preoperative radiographs help visualize the canals before treatment. Intraoperative radiographs from different angles ensure all canals are identified.

5. Iatrogenic perforations:

Cervical perforations typically result from incorrect bur direction, such as when the bur is not aligned parallel to the tooth’s long axis. During caries removal, care must be taken to avoid removing healthy enamel and dentin to prevent such complications. The depth and angulation of access bur penetration should be confirmed before proceeding with access cavity design. Perforation at the furcation is quite common. Excessive flooding of the chamber with blood should be promptly evaluated, as it often signals a potential perforation.

II. Procedural errors related to canal shaping and cleaning

Common Procedural Errors Encountered During Canal Shaping and Cleaning:

1. Canal blockage and ledge formation:

Canal blockage typically occurs due to apical compaction by dentinal debris during the shaping and cleaning of the root canal. To prevent this, instrumentation should be performed sequentially, and working length recapitulation should be done periodically. Additionally, copious amounts of irrigants should be used, and regular inspection of the files for wear is essential.

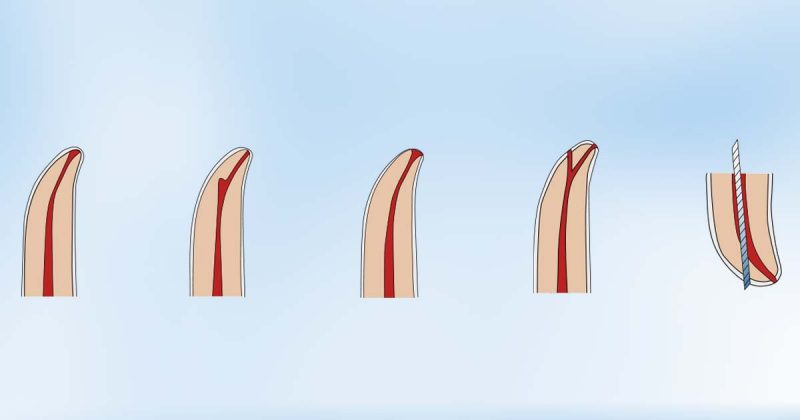

A ledge is an artificial deviation in the root canal wall that blocks an instrument from reaching the apex. It can result from misjudging canal curvature, incorrect canal length, or using straight instruments in curved canals. Ledge formation can be prevented by regular recapitulation with smaller files, maintaining canal patency, working passively, and taking accurate preoperative radiographs. Management involves using thermoplasticized gutta-percha to seal and close the canal.

2. Deviation from normal canal anatomy:

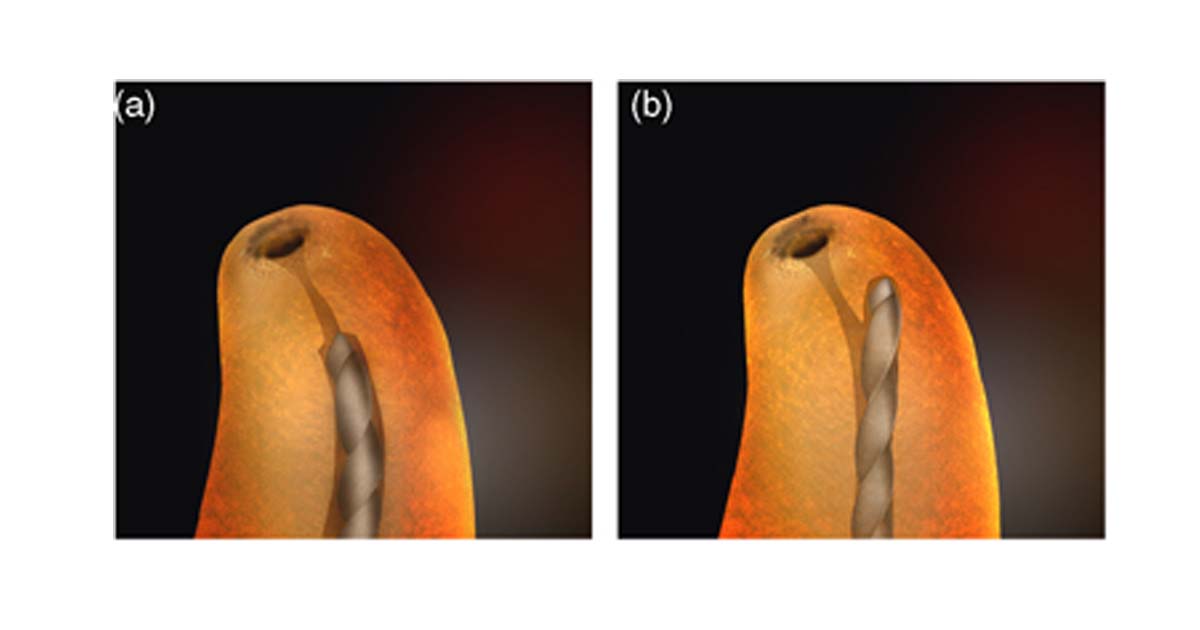

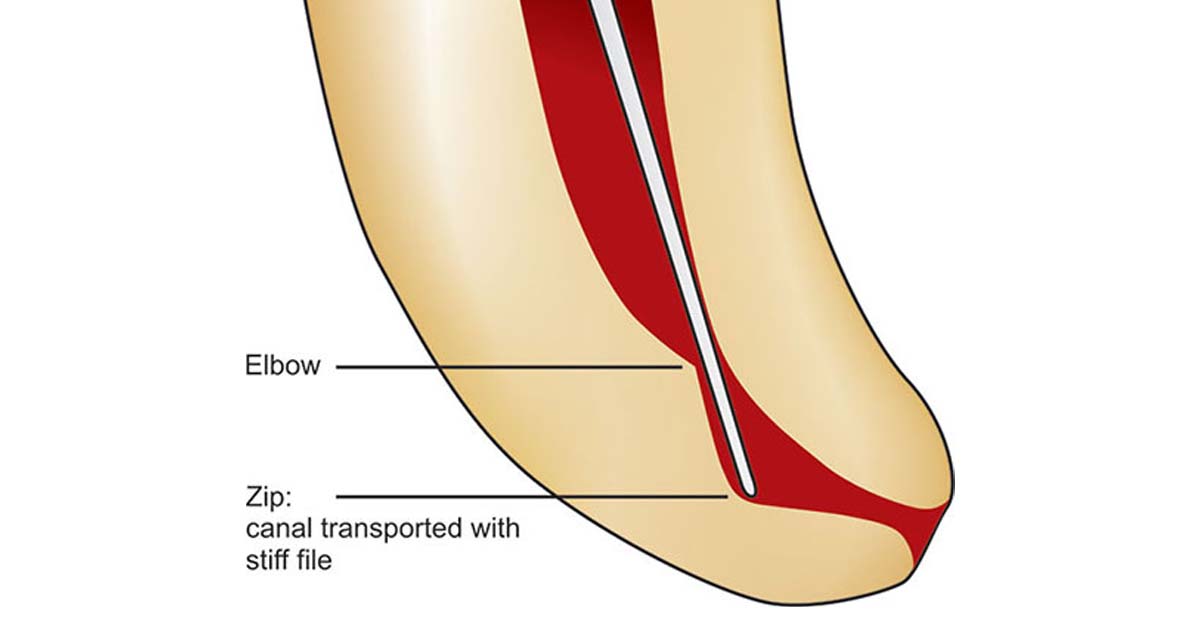

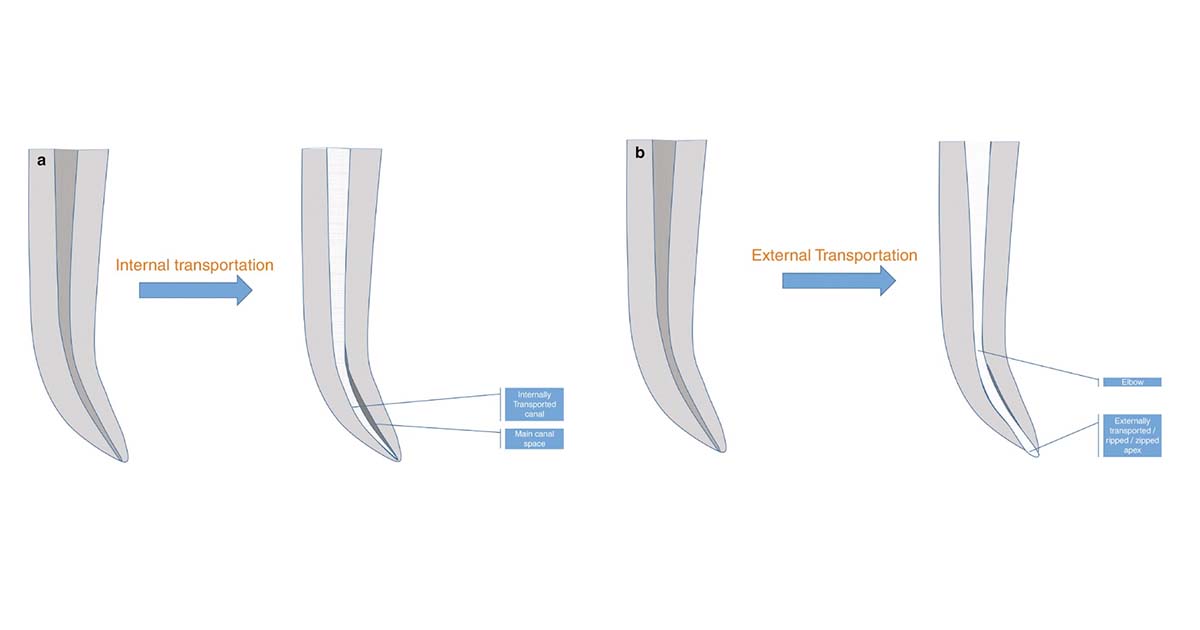

Deviations in canal anatomy can present as zipping, elbow formation, or transportation. Zipping is the apical transportation of a curved canal caused by improper shaping. Transportation is the deviation of files from the original canal path, especially with larger files. Initial shaping with smaller files minimizes this risk. Elbow formation, often with zipping, occurs at maximum canal curvature due to irregular widening along inner and outer aspects.

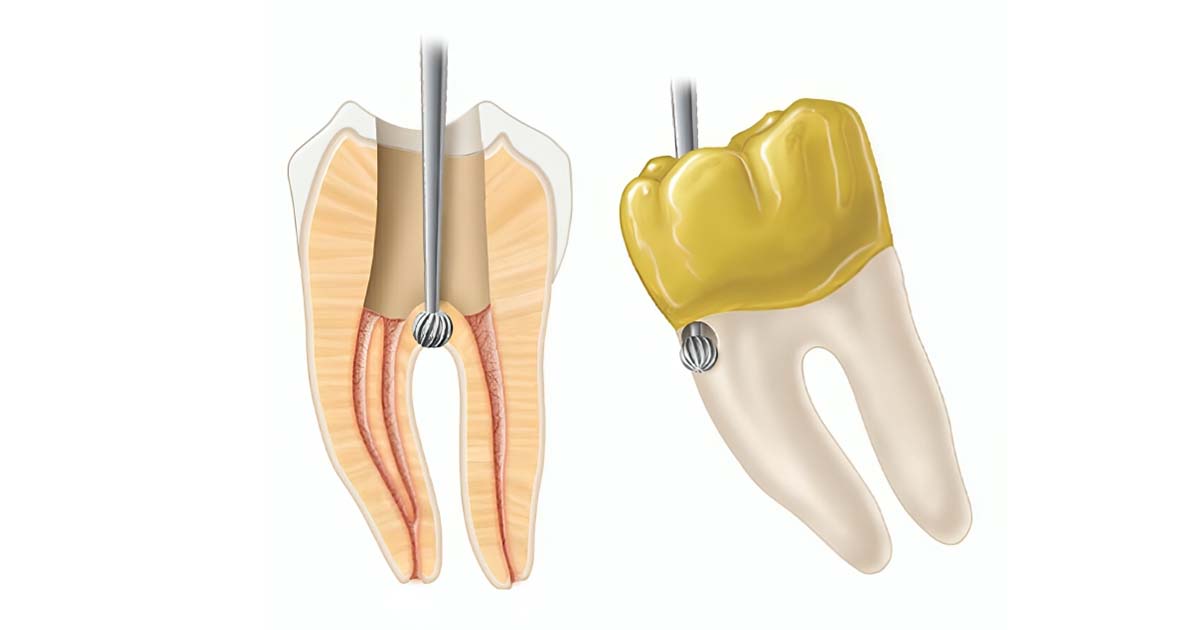

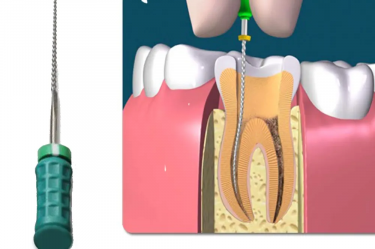

3. Separation of instruments:

Instrument separation usually happens when an instrument is forced into the dentinal structure or overused. Fracturing of an instrument in the apical third is often difficult to bypass, whereas in the coronal third, it can usually be removed or negotiated to the apex. Prognosis and management depend on the separation level, instrument size, infection severity, operator skill, patient motivation, and planned treatment. Many instrument retrieval kits are available on the market today, widely used by endodontists. These kits can be conveniently explored on our website, DentalKart.

4. Obstruction by previous obturating materials:

Retreatment of a previously endodontically treated tooth requires the complete removal of gutta-percha. This can be achieved using several techniques. These include mechanical instrumentation with H files or Gates-Glidden drills, heat to soften and sear gutta-percha, and gutta-percha solvents. Ultrasonics or a combination of these methods may also be used.

III. Procedural errors related to obturation

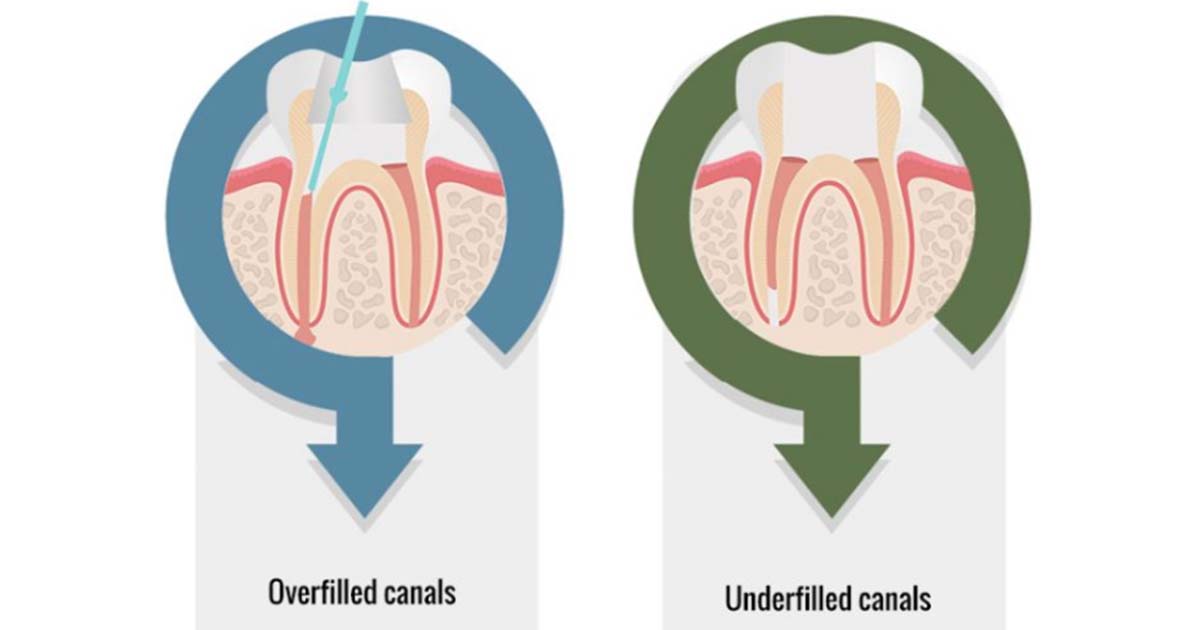

1. Underfilling of gutta-percha:

This usually occurs due to a loss of working length caused by irregular recapitulation and insufficient irrigation. A small-sized file can be used for recapitulation to help dislodge the packed dentinal mud, along with copious irrigation using sodium hypochlorite. A confirmatory radiograph with the master cone should be taken before completing the obturation process.

2. Overfilling of gutta-percha:

Overextension of gutta-percha often results from loss of apical constriction due to over-instrumentation, perforation, or inaccurate working length determination. Nerve paresthesia may result from overextension caused by overfilling. This can be prevented by accurate working length estimation using an apex locator and radiographs. The master cone should be evaluated in the apical third before proceeding with obturation. In wide canals, the master cone should be placed slightly short of the apex to flow into apical constrictions during thermal compaction. Apical stops are mandatory, and reproducible reference points must be identified and consistently followed throughout the treatment to prevent overextension.

Other related mishaps

- Aspiration or ingestion of endodontic instruments: Aspiration typically occurs when the procedure is performed without the use of a rubber dam. Such accidents can be life-threatening and may result in legal action against the dentist. This is a preventable procedural error, making it essential to use a rubber dam to avoid such mishaps.

- Tissue emphysema: Tissue emphysema is primarily caused by two factors. One is a blast of air used to dry the canal. The other is exhaust air from a high-speed drill directed into tissues during apical surgery. This results in rapid swelling, crepitus, and erythema. To prevent this, dentists should avoid blowing air into an open canal.

- Vertical root fracture: Vertical root fractures may occur due to excessive force during lateral compaction of gutta-percha during obturation. Diagnosis involves hearing a crepitus-like or crunching sound along with a pain response from the patient. These fractures can be prevented by avoiding over-preparation of the canal and applying controlled and minimal force during the obturation process.

- Irrigant-related mishaps: Common irrigant solutions, such as sodium hypochlorite, can cause periradicular tissue necrosis, particularly in cases involving an open apex. The severity of damage can range from mild to severe. Sodium hypochlorite extrusion beyond the root canal can cause chemical burns and periradicular tissue necrosis intraorally and extraorally. This can be prevented by copious saline irrigation to remove sodium hypochlorite from periradicular areas and hydrocortisone injection.

Conclusion

Root canal therapy is a cornerstone of endodontics, demanding precision and an in-depth understanding of procedural nuances. By staying aware of potential errors and implementing preventive measures, clinicians can deliver predictable and lasting outcomes. Modern endodontic equipment and techniques, available at DentalKart, help overcome challenges and improve treatment protocols.

At DentalKart, we’re committed to supporting dentists with high-quality instruments, materials, and resources to enhance clinical practice. By continuously improving skills, staying updated with innovations, and utilizing reliable products, we can elevate patient care and ensure the long-term success of endodontic treatments.

Frequently Asked Questions:

Ledging is a deviation in the root canal wall that blocks instruments from reaching the apex. It can be prevented by using smaller files, maintaining canal patency, and working passively.

Zipping is apical canal transportation caused by improper shaping. It can be avoided using smaller files for initial shaping and proper technique.

Use periapical radiographs from different angles and ensure thorough deroofing of the pulp chamber to find missed canals.

Prevent vertical root fractures by avoiding over-preparing the canal and applying controlled, minimal force during obturation.

No Comment